What is kanban really?

1 Mar 2020 11 minute read

Oversimplified and underestimated.

Kanban is not a software development life cycle methodology or an approach to project management. It requires that some process is already in place so that kanban can be applied to incrementally change the underlying process.

Kanban is most likely one of the oldest practices, as it originated in Japan in the late 1940s and was created by Toyota to improve their automotive production efficiency. Kanban in Japanese translates roughly to “billboard”, “signal card” or “signpost”, but the translation we will work with is “visual board”.

Although it is often oversimplified in its introduction, it is in fact a vast and thorough practice which can handle surprisingly complex workflows and organizations. Introducing it to an existing organization correctly can even be a daunting task for experienced managers.

Kanban has been adapted and applied in many industries and sectors, including software development and business process management. In each industry the detailed specifics may change, but the core concepts remain intact. I am not going to discuss the implementation in other sectors and will only focus on the practice as it applies to software development.

If you are interested in a deep dive into kanban for software development, I recommend chapters 2, 3 and 4 of the book: “Kanban: Successful Evolutionary Change for Your Technology Business”

The biggest issues with kanban

Ignorance and oversimplification

If someone has not been properly introduced to kanban either by self-study or an experienced project manager, what comes to mind when someone mentions a kanban more often than not is a simple board with 3 columns “TO DO”, “DOING” and “DONE” and a few tickets.

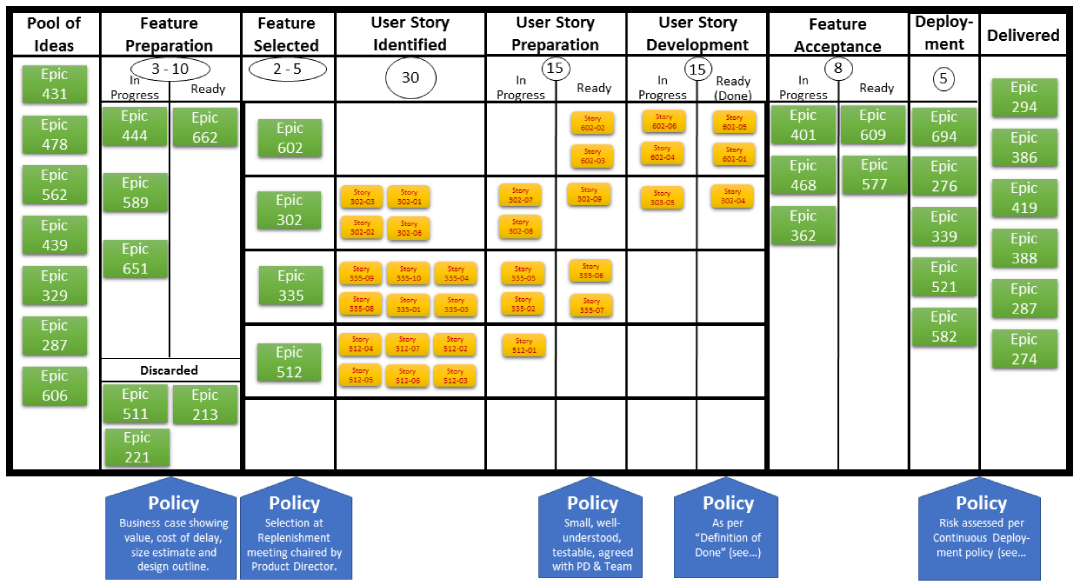

However, when kanban is introduced, it reflects the workflow of the team and, unless you are starting from scratch, you will have at least some existing organizational structure and workflow. A more realistic “image” of kanban is the example from the wiki page, as it accommodates the allocation of tasks on a board from inception to delivery:

Core concepts

Kanban does not require an overhaul of an organization; it allows any current organizational structure and workflow to remain in place as it advocates for gradual and incremental improvements.

Visualise workflow

As kanban adapts to existing structures and workflows, it is important that the team has a clear and common understanding of the existing workflows. To succeed in this pursuit, it is important to be able to visualize the workflow. By visualizing the workflow, the team can “see” what the state of the project/product is at a glance. It provides a transparent and simple manner to track any task throughout the workflow and provides a collective representation of the state of the product/project at any given moment. This creates a shared understanding of the workflow and allows the team to have more productive discussions on status and flow, as no time is wasted on misunderstandings about the state and flow of any given task.

This visualization is done most often using the ubiquitous queue board, which has been adopted by most, if not all, of the agile software development practices and methodologies.

Limit work in progress (WIP)

Limiting the work in progress often seems like an obvious step. However, it is a crucial part of kanban and should be explicitly mentioned. By limiting the work in progress, the team will be prevented from multitasking and will thus focus on a limited set of tasks from inception to delivery, thereby improving the pace at which features and requirements are delivered and met.

This practice will also make bottlenecks and workflow issues more apparent, as things are not allowed to pile up during development. Any blocking issue, task, or state in the workflow becomes easier to identify, and when the impact is measured and clearly communicated, it is easier to justify improvements.

Manage and measure flow

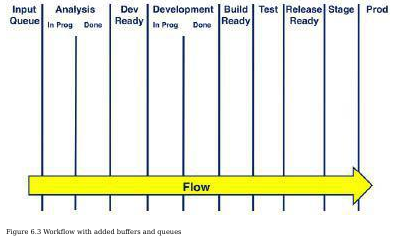

Flow refers to the changes to the state of any given artifact throughout the workflow. When visualized on a kanban board, the flow means the movement of cards from the left to the right side of the board, e.g.:

Managing the flow requires the whole team to collaborate and communicate clearly about the state changes. A change in the state of any artifact needs to be visible and done according to the policies and the defined flow. The board needs to be constantly kept up to date to reflect reality. When changes to state and flow are not accurately visualized on the board, it can lead to a multitude of problems in the workflow. It is important that every individual member of the team is dedicated to keeping the collective board up to date.

Part of managing the flow is to make alterations to the flow and board as required. A workflow needs to be able to adapt to changing business and development requirements as a team matures and improves, or the business changes. Any changes to the workflow need to be reflected in the structure and flow of the board.

Measuring the flow allows the team to accumulate empirical data on various performance aspects. This becomes more important in larger organizations where decision makers are often not directly involved with each and every team. Among many other reports and recommendations, they also rely on performance reports to make staffing and budget allocation decisions. However, measuring the flow is critically important for the team as well, as it can provide vital information that can be used to discover improvement opportunities.

When measuring the flow, it is necessary to track time, status changes, assigned team members, changes made to artifact definitions, number of tasks per state, lead time, delivery time, time spent in each state, etc. Luckily, most of the contemporary tools available to teams automatically track many of these metrics.

Make policies explicit

There should be no unwritten rules when it comes to any aspect of the team’s workflow. Policies should be collectively agreed upon and made explicit. Explicit policies can reduce issues and provide clear instructions for the team. An example is the limit on work in progress. If there is an unwritten rule that there is only one card per developer in progress, it is better to make it an explicit policy so that the team will self-enforce the policy instead of requiring the team or management to occasionally reiterate it, freeing up time. It is important to note that policies are negotiable and can change as improvements are made or requirements change. As long as policies are explicitly defined, there is no ambiguity and there is a shared reference for the way things are done.

Use models to recognise improvement opportunities.

There are many models that can be used to identify improvement opportunities, such as the Theory of Constraints (TOC) or Statistical Process Control (SPC), etc. Each of these models has its own research and literature to back it up and exists independent of the contexts the models are used in. However, they may be a little high level, and a good starting point is to at least know that these models exist.

An example of a formula for continually discovering improvement opportunities is the Five Focusing Steps which is part of the TOC model. It states:

Steps:

- Identify the constraint.

- Decide how to exploit the constraint.

- Subordinate everything else in the system to the decision made in Step 2.

- Elevate the constraint.

- Avoid inertia; identify the next constraint and return to step 2.

Step 1 is asking us to find a bottleneck in our value stream.

Step 2 asks us to identify the potential throughput of that bottleneck and compare that to what is actually happening. As you will see, the bottleneck is rarely or never working at its full capacity. So ask, “What would it take to get the full potential out of our bottleneck? What would we need to change to make that happen?” This is the “decide” part of step 2.

Step 3 asks us to make whatever changes are necessary to implement the ideas from step 2. This may involve making additional changes elsewhere in the value stream in order to get the maximum capacity from the bottleneck. This action of maximizing the bottleneck’s capability is known as “exploiting the bottleneck.”

Step 4 suggests that if the bottleneck is operating at its full capability and is still not producing enough throughput, its capability needs to be enhanced in order to increase throughput. Step 4 asks us to implement an improvement to enhance capability and increase throughput sufficiently so that the current bottleneck is relieved and the system constraint moves elsewhere in the value stream.

Step 5 requires that we give the changes time to stabilize and then identify the new bottleneck in the value stream and repeat the process. The result is a system of continuous improvement in which throughput is always increasing. If the Five Focusing Steps is institutionalized properly, a culture of continuous improvement will have been achieved throughout the organization.

Facilitating communication

Kanban was introduced into software development after the manifesto for agile software development was written and, thus inspired by the manifesto and other agile frameworks, it recommends a number of formal and informal meetings to augment the practice of kanban.

Standup meetings

Standup meetings are common among agile frameworks, as we have already noted with scrum, for instance. However, the structure of a standup meeting in kanban is very different from that of scrum. Instead of focusing on individuals and their contributions or issues over a 48-hour window, kanban recognizes that all of this information is present on the kanban board and by examining it should be obvious.

Standup meetings in kanban focus on the board, and typically a team member or manager will “walk the board” from right to left and may solicit updates on cards in case there is some information that is important but not visible on the board. Participants are also given a chance to inform the team if they are in need of assistance or whether there are any blocking tasks. Mature teams often only discuss flow issues and blocking tickets.

The after meeting

This is an informal meeting that can happen at any time, but usually some time after another meeting, and is usually between 2 or 3 team members to discuss whatever they have on their mind. Informal discussions such as these often generate valuable ideas for improvement or insights. This often leads to improving processes and innovation in general and should generally be encouraged.

Queue replenishment meetings

This is similar to the “Sprint planning” meeting in scrum. At regular intervals, the team needs to come together and prioritize cards on the kanban board backlog.

The purpose of such a meeting is to fill the kanban system’s input queue for a single value stream, system, or project. Stakeholders who have an interest in the deliveries from the team and who have items waiting in the backlog should attend this meeting. The business attendees should be as senior in their organizations as possible. More senior people can make more decisions and often have access to wider contextual information. This improves the quality of decision making and optimizes the selection process for queue replenishment.

Ideally, a prioritization meeting will involve several product owners or business people from potentially competing groups within the company. The tension created by this actually becomes a positive influence on good decision making and stimulates a healthy, collaborative environment with the software development team.

Release planning meetings

Release planning meetings happen specifically to plan downstream delivery. If releases are occurring regularly, with a cadence of, say, bi-weekly, then it makes sense to schedule the release planning activity to take place regularly. This reduces the coordination cost of holding the meeting and ensures that everyone who needs to attend will have the time available.

The person responsible for coordinating the delivery, usually a project manager, typically leads release planning meetings. Any other interested parties should be invited: This usually includes configuration management specialists; systems operation and network specialists; developers; testers; business analysts; and for all of these individual contributors, their immediate supervisors or managers. Specialists are present for their technical knowledge and risk-assessment capabilities. Managers are present so that decisions can be made.

When an organization has embraced continuous delivery and continuous integration, as is common in contemporary web-based software development organizations, this meeting becomes somewhat obsolete and can be substituted with something akin to the “Sprint review” meeting in scrum when releasing significant features or products.

Getting Started: Beyond the Simple Board

Now that we’ve explored the depth and complexity of true kanban implementation, it’s clear why the simple “To Do, Doing, Done” board is just the beginning. Kanban’s real power lies in its ability to evolve with your team and organization while maintaining focus on continuous improvement.

Key Takeaways

If you remember nothing else from this article, focus on these core principles:

Start where you are - Kanban doesn’t require a complete organizational overhaul

Visualize your actual workflow - Not an idealized version, but what really happens formally and informally

Limit work in progress - This single change can transform your team’s productivity

Make policies explicit - Eliminate confusion by ratifying with the team

Measure and improve continuously - Use data to drive decisions, not assumptions

The Continuous Journey

Kanban is not a destination but a journey of continuous evolution. The practices outlined here - from visualizing workflow to managing flow - work together to create a system that adapts and improves over time. What starts as a simple board can evolve into a sophisticated system that provides unprecedented visibility into your team’s capacity and capabilities.

Remember: the goal isn’t to implement kanban perfectly from day one, but to start improving incrementally. Each small change builds on the last, creating a culture of continuous improvement that extends far beyond the board itself.

For those ready to dive deeper into the theory and advanced practices, D.J. Anderson’s “KANBAN: Successful Evolutionary Change for Your Technology Business” remains the definitive guide. But more importantly, start experimenting with these concepts today - your future self will thank you for beginning the journey.